Political Corruption - a Persistent Global Phenomenon

By: Julian Voss

Dec 09, 2020

Today marks the International Anti-Corruption Day, which was initiated after the United Nations General Assembly adopted its Convention against Corruption in 2003. This event aims to raise awareness about the various efforts to combat corruption around the globe. Therefore, today’s weekly graph uses V-Dem data to look at the global development of corruption.

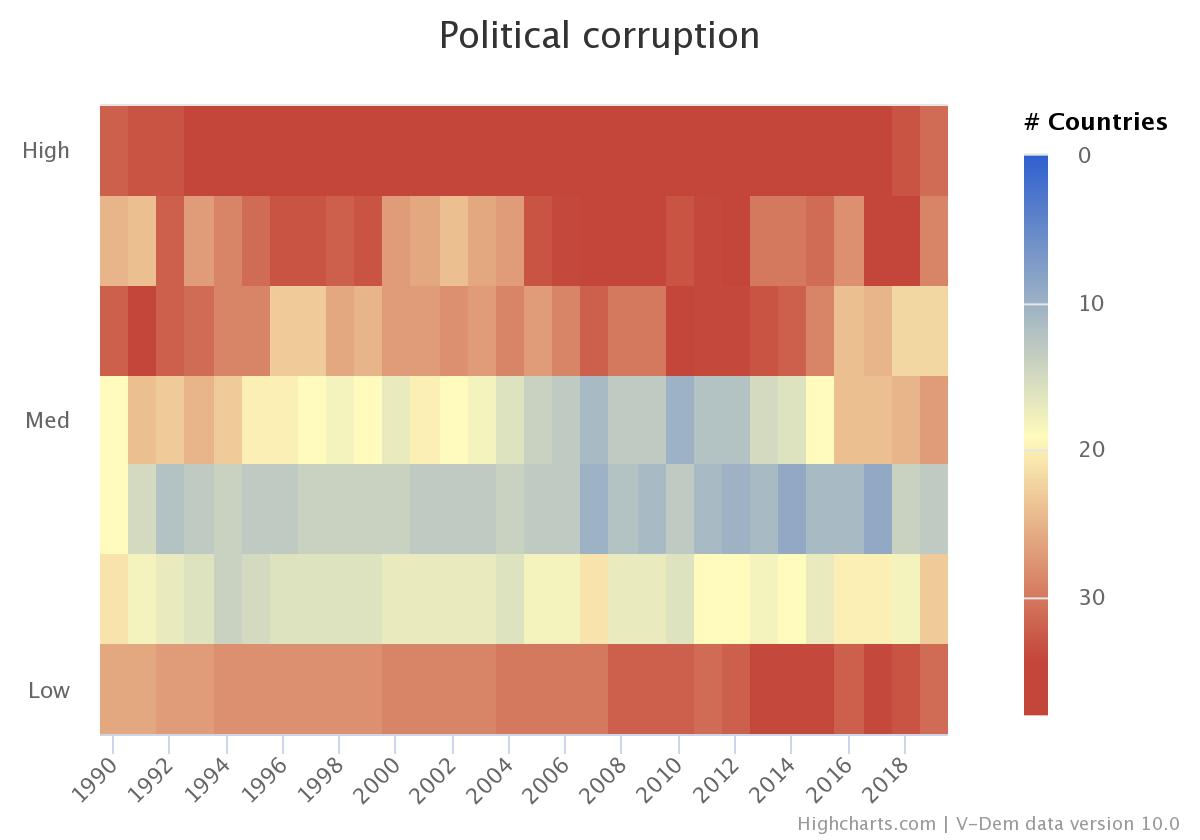

The heat map below shows the distribution of countries across different levels of the political corruption index from 1990 to 2019. This V-Dem indicator considers six different forms of corruption. It incorporates measures of corruption in the executive, legislative, and judiciary as well as in the public bureaucracy. The included measures further differentiate between bribe-taking and embezzlement within the executive and administration. Taken together, this index gives us a holistic indicator of how different types of corruption prevail for each country, in a given year.

The graph shows that there has been comparatively little change during the last three decades and most countries find themselves at either end of the corruption spectrum. Nevertheless, there have been substantial changes over time within countries. For instance, countries like Georgia, Tunisia, or Benin made considerable progress in reducing corruption. On the contrary, corruption substantially increased in Malawi, Burundi, and Albania, according to the data.

Why is it that corruption is so persistent in many parts of the world? Part of the answer lies in the nature of the problem. When corruption is widespread, it becomes institutionalized and the norm rather than the exception. In an environment where political power or access to public services depends on the payments of bribes, non-corrupt behavior can lead to considerable disadvantages. Therefore, anti-corruption efforts are plagued by collective action problems as individuals have little incentive to deviate from the expected behavioral norm. Democratic elections are often seen as an effective means of reducing corruption because elected officials will fear being sanctioned at the polls if they misuse their position for private gains. However, even holding competitive elections is often not enough to curb corruption as voters may lack access to reliable information that is required to blame the responsible individuals. Furthermore, voters have little chance to disincentivize corruption in the absence of real alternatives. This issue is illustrated by cases like Ghana or Indonesia, which made extensive progress in election quality, but where corruption levels are still high, according to the data.

The fact that corruption is still widespread in large parts of the world should not discourage anti-corruption efforts. International organizations engaged in the fight against corruption should evaluate their strategies against the background of successful cases and continue their support for democratic actors trying to hold corrupt officials accountable. Research projects like V-Dem can contribute to these efforts by refining their measures and increase our knowledge about the past and present.

To learn more about the state of corruption or other related topics, go to www.v-dem.net.