Corruption in South America

By: Ana Laura Ferrari

Nov 16, 2020

The effective provision of public goods depends on how public authorities spend tax money. However, in many countries, misappropriation of state resources by public sector employees undermines public goods provision. Denouncing this kind of corruption can be dangerous. For example, Fabián Gutiérrez, a former secretary to Argentina’s ex-president Cristina Kirchner, was murdered in June 2020. He was a "collaborating witness" with Argentina's prosecution in a case that involved public works projects, raising concerns that the crime was aimed at eliminating a key witness in the case.

Corrupt businessmen and bribe-seeking officeholders have always been part of South American countries' political landscape. Recently, however, several investigative efforts were made to address the issue. In Brazil, Operation Car Wash revealed how political parties supported construction firms in public biddings in exchange for campaign donations. These efforts to uncover corruption led to discoveries of public sector corruption in other countries as well. In Paraguay, Colombia, and Peru, for example, businessmen received undue advantages from government officials in exchange for bribes for decades.

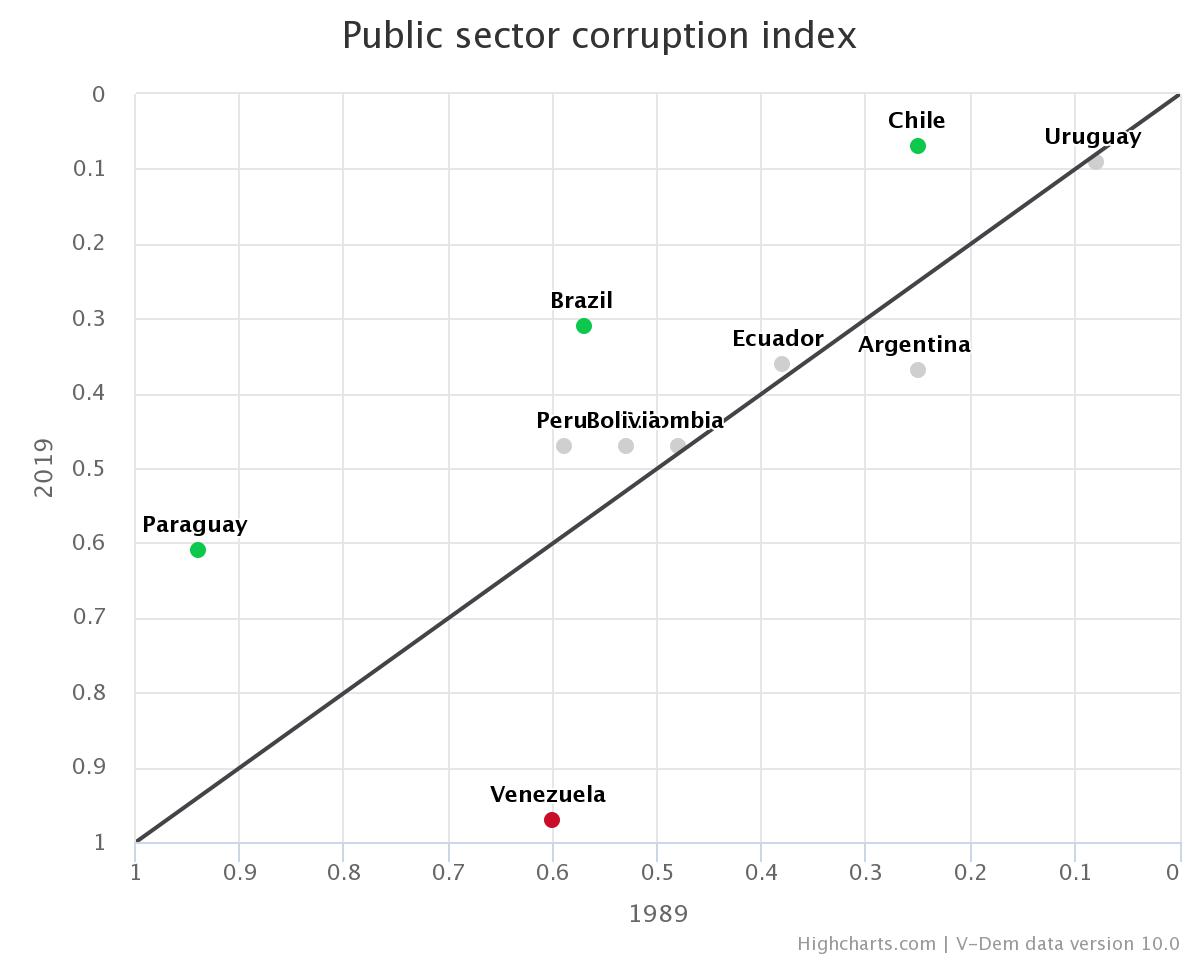

The graph below shows a comparison of V-Dem’s public sector corruption index for South American countries between 1989 and 2019. The index measures the extent to which public sector employees grant favors in exchange for monetary advantages or steal public funds for personal uses. It ranges from 0 to 1, with lower scores indicating less corruption, and higher scores indicating more corruption. In the graph, the countries located above the diagonal line have less corruption in 2019 than they had in 1989. On the contrary, countries below the line have more corruption today than in 1989.

Four countries stand out: Paraguay, Brazil, Chile, and Venezuela. The first three saw several corruption scandals coming to light in the last decade. However, this does not necessarily mean that bribes have become more frequent. It might be the case that more corrupt individuals were caught, raising the costs of engaging in corrupt activities. Indeed, the data suggests that fewer public officials commit corruption today than three decades ago.

The only case in which corruption substantially expanded is Venezuela. This development is not surprising as the country has moved towards electoral authoritarianism and state institutions are under partisan control. Corruption scandals usually come to light when control institutions have the power to investigate independently. As the police and the judiciary respond to party interests in Venezuela, public sector employees take advantage of public funds more often today than in 1989.

The increasing prosecution of corruption in South America has not been without problems. There are cases in which control institutions violated defendants' legal rights. In Brazil, for example, one of the main federal judges involved in Operation Car Wash worked in collaboration with prosecutors, which is a clear violation of criminal procedures. Despite these objections, the hope is that prosecuting corruption and punishing perpetrators reduces the incentives for corruption in the long-term and increases citizens' confidence in their governments.