Elections in Kyrgyzstan – A Backlash against Democracy?

By: Julian Voss

Jan 26, 2021

On the 10th of January Kyrgyz voters elected Sadyr Japarov as the country’s new president and voted in favor of a shift from a parliamentary to a presidential political system. This election marks the end of a political reshuffle that began in early October, when violent clashes between demonstrators and security forces surrounding the Kyrgyz presidential election led to the resignation of former president Sooronbay Jeenbekov over allegations of electoral fraud. Japarov, a renowned political figure, was freed from prison by demonstrators during the October events and has initiated the controversial constitutional reform while putting his name forward for the presidential elections. Today’s weekly graph will put these recent developments into context with the help of V-Dem data.

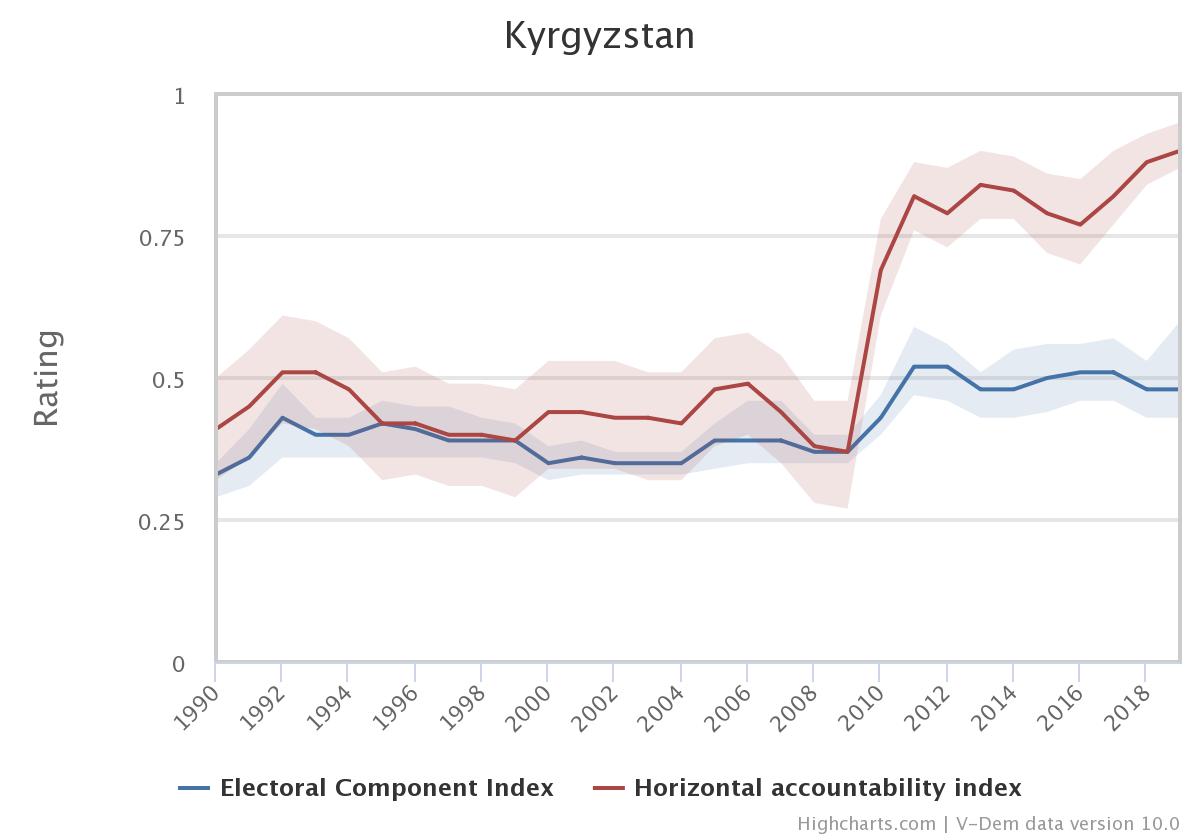

The graph below shows the evolution of two V-Dem indicators for Kyrgyzstan between 1990 and 2019. The electoral component index measures the extent of accountability between political decision-makers and the citizenry through competitive elections. It considers suffrage, freedom of organization for political and civil society groups, the degree of electoral irregularities, and the executive’s direct or indirect appointment by an election. The horizontal accountability index measures institutional checks on the executive through the legislature, the judiciary, or other oversight institutions. Both indices take on values between 0 and 1, where higher values indicate greater accountability.

Kyrgyzstan’s first experiments with democracy began in the 1990s when the former Soviet republic gained independence. After an early phase of political and economic liberalization, the country’s first President Askar Akayev increasingly governed by autocratic means. As the data show, both the electoral component index and horizontal accountability remained relatively low for the first 15 years after the end of the Cold War. The presidency of Akayev ended in 2005 during the so called “Tulip Revolution”, one of the “Color Revolutions” across the post-Soviet space. However, unlike the events in Georgia and Ukraine, the Kyrgyz movement did not bring about substantial improvements in democratic reforms, and both V-Dem indicators show little change during this period. Only a second upheaval in 2010 brought about sustained institutional change as demonstrated by improvements on both indicators.

The October crisis in Kyrgyzstan can already be viewed as the result of a lack of vertical accountability. The centralization of political power could further destabilize the country as opposition elites from the south might be more inclined to resort to extra-institutional means of wielding power. As a majority of voters accepted the return to presidentialism in Kyrgyzstan, there seems to be little resistance to the reorganization of the country’s political system. At the same time, several domestic politicians and international organizations criticized the proposed constitutional draft. They expressed concerns about the shift of executive power towards the presidency, the weakening of parliament, and provisions that might restrict media freedoms. Therefore, the latest elections can offset some of the improvements regarding accountability mechanisms and have important implications for the future of democracy in Kyrgyzstan.