Political Polarization after Democratization on the Iberian Peninsula

By: Cristina Schaver

May 25, 2021

Portugal and Spain have parallel histories going back centuries. Portugal has the oldest territorial boundaries in Europe––defined in relation to Spain––and both nations have at turns been colonial powers, kingdoms, republics, and, during the middle half of the 20th century, dictatorships.

Portugal’s return to democracy began with 1974's Carnation Revolution, which ended the Estado Novo (“New State”) corporatist regime which took power in 1933. The April 1976 proclamation of a new Constitution consolidated democracy. Spanish military dictator Francisco Franco died in November 1975, after 39 years in power. His death reinstated the monarchy with King Juan Carlos as his successor. Juan Carlos put in motion a transition to democracy that culminated in a 1977 general election and a new Constitution, approved by referendum in 1978.

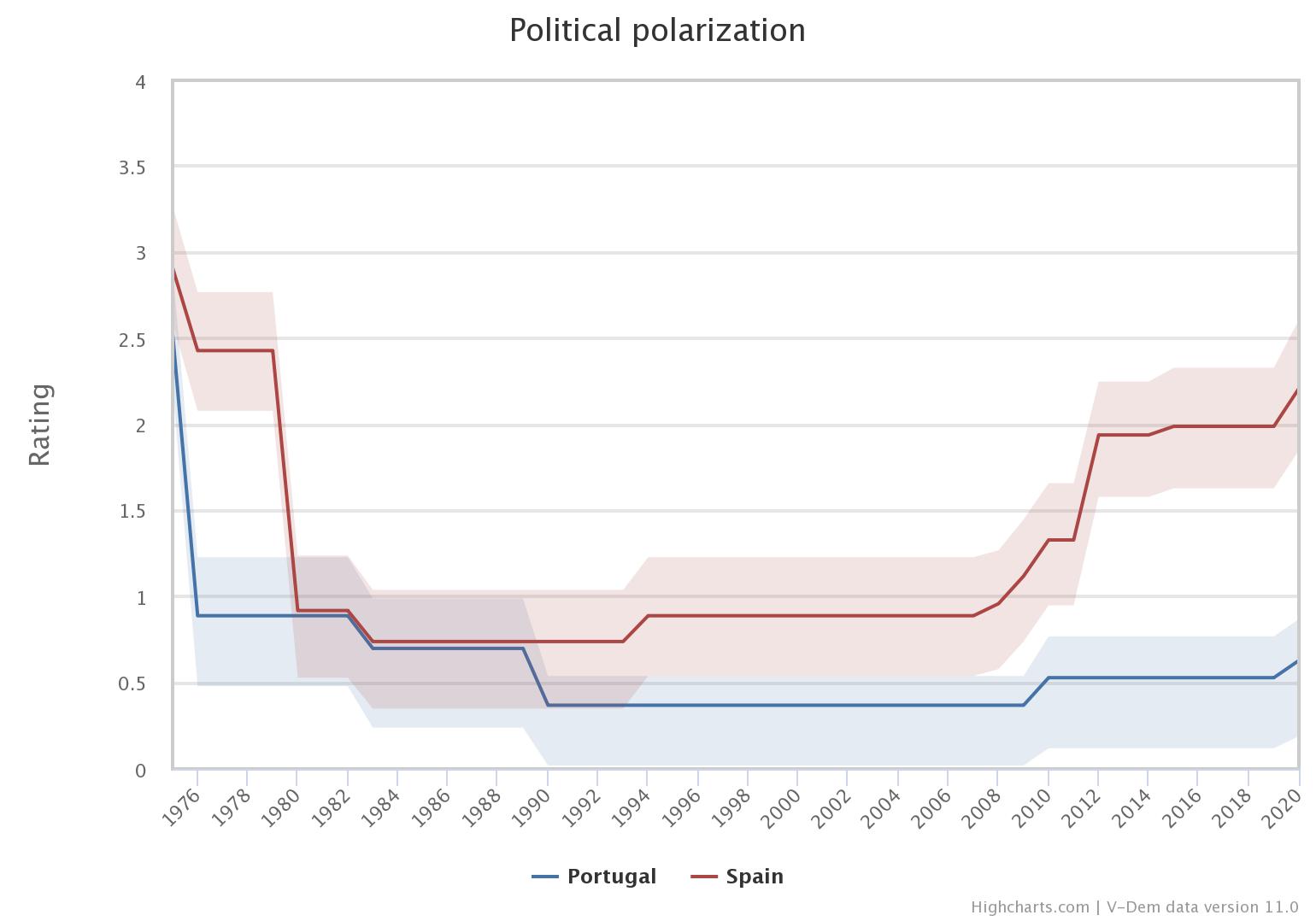

Since then, both countries have maintained stable democracy. However, polarization has increased: the graph shows the evolution of political polarization in Portugal and Spain from 1975 to 2020. This variable is scaled from 0 (low) to 4 (high). Both countries were polarized prior to their transition to democracy, after which polarization dropped significantly and supporters of opposing political camps became much more likely to engage in friendly (rather than hostile) interactions with each other, from family functions to workplaces.

Spain is now the most politically polarized it has been since the reconsolidation of democracy, 40 years ago. The backdrop to this increasing polarization is a protracted recovery from the financial crisis, compared to Portugal (and most EU NUTS 2 regions). Unemployment across many euro-area countries peaked in 2014––when Spain’s rate was 10 points higher than Portugal’s. In 2019, most Portuguese regions had an employment rate of 75% or higher, while employment in most Spanish regions varied between 65 and 75%.

In addition to economic stagnation, the last few years in Spain have been marked by internal political divisions, most notably coming to a head during the attempted independence referendum in Catalonia on October 1, 2017. While leaders of the “procés” have received prison sentences, separatist parties now represent amajority of seats in the Catalan regional parliament.

Polarization often precedes autocratization, and may incentivize citizens and political actors to endorse non-democratic action. V-Dem data shows a negative relationship between the level of political polarization and liberal democracy ratings. Moreover, polarization may erode the electorate’s ability to resist authoritarianism, and this rise in Iberian political polarization is taking place against the backdrop of a global rise in authoritarianism. Addressing political polarization could increase southern European democracies’ resilience to democratic backsliding.