The Future of Bolivia’s Democracy

By: Ana Laura Ferrari

Oct 20, 2020

After two postponements, Bolivians headed to the polls on October 18 to elect a new president. The political climate around the election was tense, with a massive presence of troops on the streets and fears of fraud. Although no official results had been published at the time of writing, private exit polls suggested that Luis Arce from the Movement Toward Socialism party (MAS) won in the first round against his main competitors Carlos Mesa and Luis Camacho.

Bolivia's 2020 election followed the previous presidential election in October 2019. At that time, the former president Evo Morales (MAS) was running for his 4th term. In the aftermath of the voting day, the Organization of American States' audit (which is disputed) stated that the election had been fraudulent in favor of Morales. Consequently, massive protests erupted.

Subsequently, the military intervened. Resembling Latin America's authoritarian past, the army chief Gen. Williams Kaliman asked for Morales' resignation. Morales fled the country and the vice-president and the leaders of the Lower house and the Senate resigned. Jeanine Áñez, then Senate's second vice-president, assumed the interim presidency – and held on to it until this month.

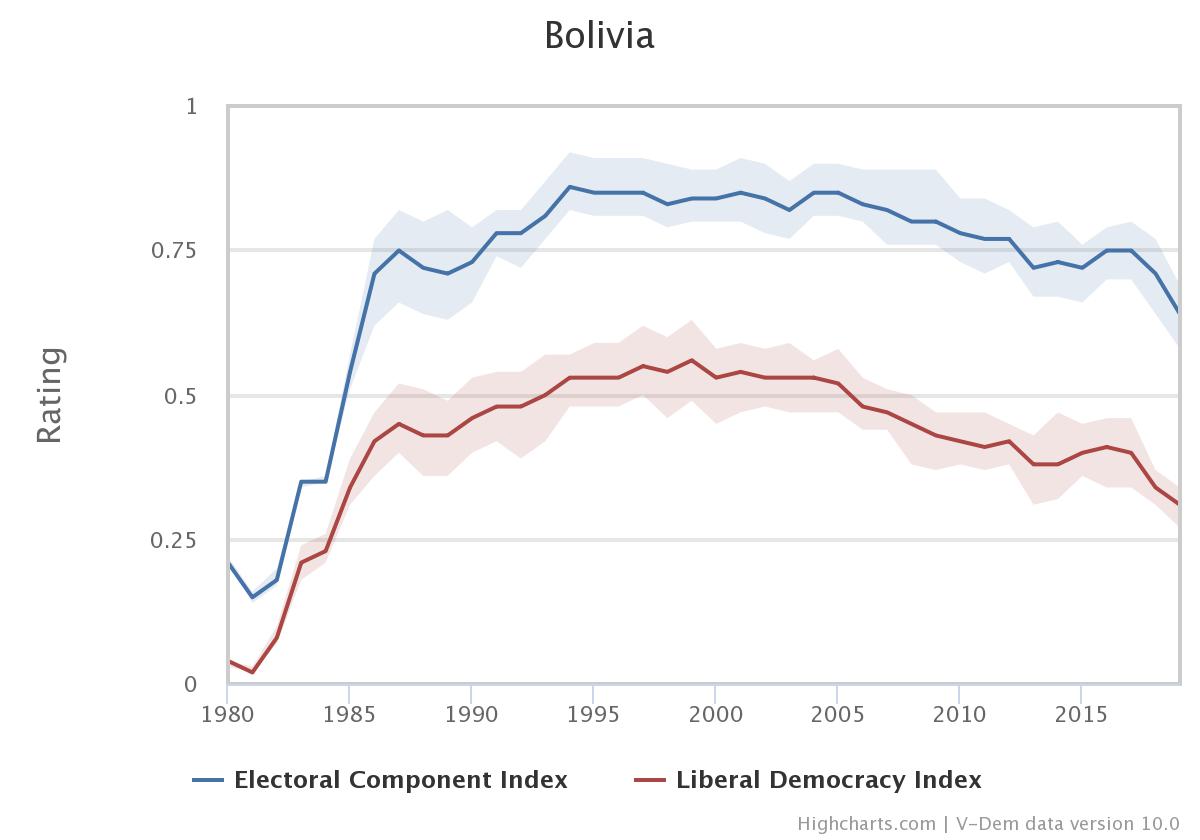

Bolivia's relationship with democracy is troubled. The graph below shows the evolution of two V-Dem indices from 1980 to 2019: the Electoral Component Index and the Liberal Democracy Index. The former measures the extent to which leaders are responsible and accountable to citizens through the existence of competitive elections. Among other things, it reflects the fairness of elections. The latter describes the extent to which the ideal of liberal democracy is achieved in a given country. It covers the guarantee of civil liberties, the rule of law, effective checks and balances and more. Together, these indices show Bolivia’s democratic record.

As the graph shows, both indices improved quickly in the 1980s - after a long experience of sequential military coups that started in 1964. From the 1990s onwards, the quality of democracy gradually enhanced. The country held competitive and multiparty elections and the protection of political rights improved. However, from the mid-2000s onwards, the indices started to drop again. During Morales's terms, elections became less reliable, and indicators such as freedom of association and expression fell.

On the one hand, Morales's first election in 2006 integrated Bolivia’s neglected indigenous population into politics. On the other hand, Morales took controversial measures when in office. For example, he got the approval from the Supreme Court to run for his 4th presidential term in 2019, even though the Constitution foresees term limits and the population rejected his plans in a referendum.

The 2020 election is a glimmer of hope that democracy will get back on track after one year of Áñez' interim government. If the results prove reliable and are accepted by all political actors, we may expect that Bolivian parties return to respecting democratic rules and norms.